-

Banded Argiope: September Spider Watching

On September mornings, as soon as I complete a check of migrating warblers, I walk through the prairie wildflowers looking for spider webs.

When there has been rain during the night or the plants are wet with morning dew, the moisture-covered webs are quite visible, especially when one walks toward the sun.

My favorite webs are the large circular webs made by orbweavers.And my favorite ordweaver species is Banded Argiope (also known as Banded Garden Spider). It is present in Eliza Howell Park every September.

Banded Argiope is a diurnal hunter and, different from many other spiders, is often visibly present in middle of the web. It hangs head down, seen here from both sides.

It holds its legs together as it waits motionless, almost looking as though it has only 4 legs instead of 8.

The vibration of the webbing tells it that a flying insect has hit the snare, It then moves with amazing speed to grab the prey and immobilize it before it can break free, wrapping it quickly in silk.

I was web watching recently * when the spider suddenly sped to a Milkweed Bug that had hit the web, quickly securing it for later consumption. (* I thank Kathy Garrett for first calling my attention to this particular web location.)

It was still at this task when a Yellowjacket struck another part of the web. It was on that instantly.

Until the spider is ready to eat, the prey hangs from the web, usually near the center. When I left a short while after it had successfully caught two sizable insects, the spider was waiting for something more, not yet indulging.

In this photo, the Yellowjacket can be seen attached to the web above the spider, the Milkweed Bug below.

Many times I just admire the webs, which the spiders reconstruct every night. When the web is wet, the design is visible and fascinating. It is (nearly) invisible when dry, not seen by the insects that fly into it.

One report claimed that Banded Argiope orient their webs on an East – West axis. I have only observed a couple of their webs since reading that report and these two webs did fit the described pattern. I will need to see more, however, before I feel confident determining directions from these webs on a cloudy day in an unfamiliar location. If correct, this would add to the fascinating behavior of a favorite September spider.

-

Snapping Turtle Hatchlings

As I reported at the time, I was able to observe a Snapping Turtle lay and bury eggs in the ground near a bench in Eliza Howell Park in June this year (“Snapping Turtle Lays Eggs,” June 15, 2022).

Ever since, I have been keeping an eye on the spot. According to published reports, many Snapping Turtle nests are preyed upon by predators such as raccoons and skunks. The ground covering this nest has remained undisturbed since June, suggesting that incubation was proceeding on schedule.

I have also been keeping an eye on the calendar. Typically, Snapping Turtle eggs hatch approximately 80 to 90 days after laying. Starting a few days before 80 days, I have been doing a quick check in the morning, expecting that the hatchlings would emerge during the night.

Yesterday was day 80 and I could see as I approached that the ground was no longer undisturbed.

The baby turtle slowly emerging was dirt-covered and appeared to be a little less than 2 inches long. The size of the hole suggested that other hatchlings had preceded it to the surface.

During the 30 or more minutes that I was watching, I did not see any more newly hatched turtles emerge from the ground, but there were a few others walking through the grasses and wildflowers. I may have arrived just as the last one was leaving the nest.

Adult Snapping Turtles, with their large hard shells, are at low risk of predation and often live for decades. Baby Snapping Turtles, however, have soft shells, a non÷threatening snap, and are very vulnerable to being eaten by mammals, birds, or snakes as they move slowly toward water. And when they reach water, they might be preyed upon by fish or other turtles. The majority reportedly do not survive the first year.

Mom and Baby I don’t know how many Snapping Turtle eggs there were in this nest or how many hatched beyond the few observed. Nor do I expect to know what happens next to these little reptiles. The last I saw they were moving slowly but steadily toward whatever their future will be.

This has been a first ever experience for me, to observe both the egg laying and the hatchlings. Repeated visits continue to reveal more of the natural wonders of Eliza Howell Park.

-

Fiery Skipper: A Small Colorful Surprise

This week I spotted the 35th butterfly species of 2022 in Eliza Howell Park, a little orange and brown/black skipper that I did not recognize immediately. It was nectaring on Chicory.

The many species of small skippers are often hard to distinguish (for me), so I photographed it to help with later identification.

It was in no hurry to move on, so I got more than one view.

After narrowing it down to a couple possibilities using field guides and online photos, I sent my photos to a couple people in the Michigan Butterfly Network who have helped me in the past. They identified it as a Fiery Skipper, a species that is not usually seen in Michigan, though it does show up once in a while.

This map of its range is taken from the Kaufman Field Guide to Butterflies of North America.

The dark green area is the area in which it is common, a very long way from Michigan. The lighter green shaded section is the area in which the Fiery Skipper is also found, but not as frequently. The additional area included by the dotted green line indicates the extent to which it sometimes wanders in late summer. We are in this occasional area, where “uncommon” overstates its frequency.

The very next day I saw another butterfly in another section of the park, also on Chicory. It too is a Fiery Skipper.

Some butterflies are sexually dimorphic (females and males look different). Fiery Skipper is one. The second one I saw this week, in the two photos immediately above, is a female. The previous day’s find was a male.

In the next picture, the two are shown together. The female clearly has more extensive dark markings.

The Fiery Skipper is very small (its body is about an inch long) and has noticeably short antennae. It is not only unusual; it is very attractive. A wonderful surprise!

-

Insect Watching: A Late August Photo Report

While I check to see if there are any migrating warblers present first thing in the morning these days (there are!), most of my focus is on the colorful insects now active in Eliza Howell Park in Detroit.

A good place to look is in a patch of flowering Goldenrod.

Ailanthus Webworm Moth

Goldenrod Soldier Beetle

Northern Paper Wasp? It is a challenge to recognize all of the many different wasp and bee and fly species visting goldenrods (beyond my ability at present), leading me to look to see what other insects are present.

Locust Borer

Chinese Praying Mantis It is hard at times to move on from the goldenrod patches, but further wandering almost always leads to additional insects to admire.

Large Milkweed Bug on Common Milkweed

White-marked Tussock Moth (caterpillar)

Yellowjacket on Oak Bullet Gall Perhaps the highlight of the past week was the sighing of a butterfly species that I have not seen in the park before — a Variegated Fritillary. It is not common in southeast Michigan and I was in the right place at the right time.

Variegated Fritillary on Purple Coneflower The insects in late August are varied and fascinating. And then there are the spiders.

But that is another report for another time.

-

Bumblebees: The Fascinating Lives of Common Pollinators

All season long, as long as there are flowers blooming, I can watch bumblebees on any nature walk in Eliza Howell Park. They take both nectar and pollen from a wide variety of flowers.

This week many of them are visiting goldenrods, which are beginning to produce abundant blooms..

I am also seeing them on Pilewort, a flower that hardly opens.

My 2022 bumblebee photos show them pollinating a wide variety of flowers — Lupine, Common Mullein, Wild Bergamot, Chicory,

another type of Goldenrod, Purple Coneflower, Culver’s Root, and Swamp Milkweed.

There are perhaps 19 species of native bumblebees in Michigan, though not all in this part of the state. They are almost all easily recognized as bumblebees, though it it is not easy to distinguish one species from another. And it is not necessary to do so, since they all live similar lives.

Bumblebees are social or colony insects, living in large nests (perhaps up to 400 individual bees) with a queen.

Each spring new queens (mated the sunmet/fall before and the only bumblebees that survive the winter) start new colonies. The first young are female workers. who take over meeting the needs of the next young as the queen continues to lay eggs.

For most of the season, there are only females. Only females carry pollen back to the nest, using the pollen baskets on the sides of their back legs (often looking orange or yellow when filled). Males have no such baskets

Only females are capable of stinging, just as only females can collect pollen

In fact, there are no males around at all till late Summer, when the queen produces males and fertile females, in preparation for the next year.

The males leave the nest, looking for fertile females from another colony to mate with. They nectar for food for themselves, but do not collect pollen for the nest. and probably do not return to the nest at all.

Recently I came across a pair of bumblebees mating (on Wingstem flowers). This was a rare opportunity to observe a male bumblebee, which can be seen to be considerably smaller than the female-to-be-queen.

At the end of the season, the old queen dies, the female workers die, the males die. Only the fertilized future queens seek locations to hibernate

—–

Everyone on group nature walks seems to recognize bumblebees. But most, I suspect, do not know that they are great pollinators or know much about their lives as social insects.

Not every species widely recognized is widely understood.

-

Butterfly Colors Fade with Age

By the time butterflies become flying adults, they have already gone through three previous stages: egg, larva/caterpillar, and pupa. In most butterfly species, adult lifespan is short, perhaps two to four weeks.

There are exceptions, such as Monarchs that migrate in the fall and Mourning Cloaks that spend the winter in hibernation as adults, but the exceptions are few.

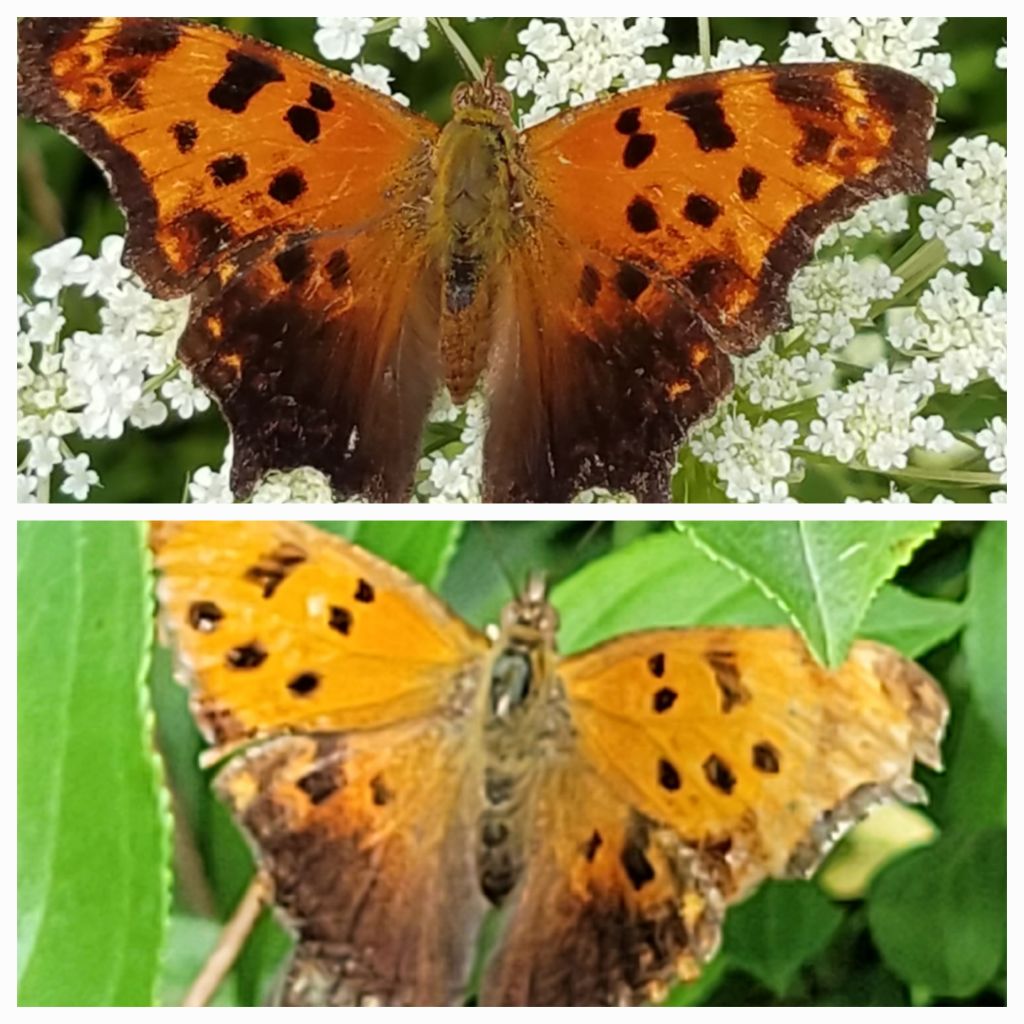

As butterflies age, their colors fade and, often, their wings become ragged. While I usually prefer to use photos of brighter colored younger adults, doing that exclusively can misrepresent what is seen in the field.

Here are some examples of how butterfly color fades.

Red Admiral

Common Buckeye

Viceroy As I watch butterflies summer after summer, it has become clear that their short life is not as easy as it might appear to someone who watches them flit from flower to flower.

Silver-spotted Skipper

Monarch

Eastern Comma Tiger Swallowtails have been abundant this summer in Eliza Howell Park; I have been seeing several almost every visit. It is easy to think that I am seeing the same ones repeatedly, but, according to the information I have seen, each lives only two weeks as an adult.

Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Perhaps it is partly because I recognize my own aging, but I am learning to admire butterflies even when faded and torn.

-

August Attractions

Following the intense nature watching months of May, June, and July here in Elza Howell Park, it can be tempting to take a break. And I do in the sense of scheduling very few group nature walks at this time of the year.

But the annual cycle does not slow down and August has its own major attractions. If someone is wondering what nature is offering here this month, these are a few examples.

1. Wild Black Cherries ripen and are eagerly consumed by birds.

Cedar Waxwings

Photo by Margaret Weber2. Ironweed, a tall and brilliantly-colored flower, reaches its seasonal peak.

3. August is a good time to start observing some of the fascinating webs and hunting behaviors of spiders.

Yellow Garden Spider

4. August is also a great time to learn more about the variety of grasshoppers and about their behavior.

5. This is (finally) the month to see the distinctive flower of Groundnut, a perennial vine.

6. Later this month, a variety of goldenrods will be in bloom, attracting many insects. One of them, Praying Mantis, patiently preys upon others.

Ailanthus Webworm Moth

Praying Mantis This is just a sample of what August presents in Eliza Howell Park. And by the end of the month, Fall bird migration will be underway. It is definitely not a month to miss.

-

A Gall Gallery: Fascinating Insect Galls

Insects are amazing. Some are able to stimulate plants to grow a shelter for their developing larvae. These growths on plants known as galls.

After the eggs that are laid on the plant hatch, the larvae start to eat. The chemical compounds they secrete stimulate the unusual plant growth.

Since discovering an additional type of gall in Eliza Howell Park, this seems a good time to showcase several kinds found here. (Kathy Garrett, another Eliza Howell nature enthusiast, called my attention to the fact that the word “gall” is found in the word “gallery.”)

Sumac Leaf Gall This gall is the most recent find. It is on some Staghorn Sumac shrubs. Inside the galls are developing aphids.

Sumac Leaf Gall Near the river each summer are patches of tall Cutleaf Coneflowers (also called Green Coneflowers).

Cutleaf Coneflower At the base of the flower on some of these coneflowers are large galls, made and inhabited by tiny midges.

Rudbeckia Gall

Rudbeckia Gall A fascinating gall is occasionally seen on wild grape vines. It resembles a bunch of filberts or hazelnuts and each is a midge “nest.”

Grape Filbert Gall Every year, I find small growths on the midrib of different white oak species. They are present now and will remain until fall. These galls house young wasps.

Oak Leaf Hedgehog Gall While most species of goldenrod are not yet blooming, they are growing rapidly. Some stem insect galls can already be seen.

Goldenrod Gall These galls are home to eggs and larvae of a type of fly and are often easier to find in the winter when the leaves — and the larvae — are gone.

Goldenrod Gall The stems of Swamp White Oak or Bur Oak are sometimes the location of a different wasp gall, Oak Bullet Gall.

Oak Bullet Gall These wasps are able to stimulate the oak to ooze sweet sap, attracting other insects to patrol the galls and prevent attack by predators.

Oak Bullet Gall The last stop on today’s tour of the gall gallery is at photos of blackberry canes, where I often find a small number of large galls on stems. These are also the home of small wasps.

Blackberry Knot Gall

Blackberry Knot Gall Every year — more like every week — I become more and more impressed by the wonderful world of insects. Tiny unidentified flies and wasps and aphids and midges stimulate the growth of galls — and stimulate as well as my sense of wonder.

-

The Different Among the Familiar: The Past Week in Eliza Howell Park

After more than 2000 nature walks in Eliza Howell Park, I have learned what to expect at various times of the year. It has been both exciting and sarisfying this past week to observe many the same colorful wildflower and butterfly species that I usually see in mid to late July.

It is also true, though, that I will frequently see something new, even after all these visits. This week there were three notable first-time observations.

This is the first time that I have seen an American Snout in Eliza Howell Park. A Snout is a butterfly more often seen south of here, not at all common in southeast Michigan.

It only takes a quick look to understand the origin of its name! The very familiar Wild Bergamot is being visited by a different kind of butterfly.

As I was checking some of the many Common Milkweed plants for signs of Monarch larvae, I noticed that something else has been eating the leaves. Monarch caterpillars eat the whole leaf. This “something else” left the veins.

I will now be looking to find these caterpillars in action. Until I find them, my identification is tentative, but I suspect that these leaves were eaten by small Milkweed Tussock Moth caterpillars. I have seen adults, but have not yet seen the larvae on milkweed leaves.

As I was looking to see how the fruit of the Hawthorn trees is developing. I saw that some of the hawthorn apples are this year hosting a fungal growth.

This is also something that I have not previously seen in the park. It looks to me to fit descriptions of Cedar Quince Rust fungus. This fungus reportedly does not typically do long-term damage to the trees.

It’s fascinating.

Most of my time and attention this week remained on the seasonal highlights that are here each year.

It was a week of great butterfly watching. Butterflies are most approachable when they are nectaring.

From top left clockwise: Viceroy at False Sunflower, E. Tiger Swallowtail at Purple Coneflower, Cabbage White at Canada Thistle, and Silver-spotted Skipper at Wild Bergamot.

Flower watching was good this week even when no butterflies were present.

Yellow Coneflower

Joe Pye Weed behind False Sunflower I always enjoy watching bumblebees collect orange or yellow colored pollen in the “baskets” on their hindlegs.

Among the many visible insects these days are dragonflies. The large Twelve-spotted Skimmer is one of my favorites.

Female

Male Nature is predictable and nature is often surpring. Most sights are familiar; some are new. Both the familiar and the new please and educate.Together they keep me coming back, even on these hot summer days.

-

Viceroy: A Butterfly Equal to the Monarch

This is the best time of the year to enjoy butterfly watching in Eliza Howell Park. Many meadow flowers are in full bloom, attracting a colorful variety of butterflies.

One species now present is often misidentified: the Viceroy butterfly. It looks very much like the much better known Monarch, so a quick look leads many to think it is a Monarch.

Viceroy It is slightly smaller than a Monarch, but the major visible difference is the black line across the hind wings.

Monarch Even in name, the Viceroy is subordinate to the Monarch. In colonial history, a “viceroy” is someone who exercises authority in the name of a sovereign, a “monarch.”

Viceroys arrive in the park in July and, as I watch them this week, I find myself thinking that they deserve to be recognized as special on their own, not just thought of in relationship to Monarchs.

Viceroy on Wild Bergamot

Viceroy on Queen Anne’s Lace Viceroys do not migrate; rather, they spend the winter as caterpillars. They can be found in most parts of the U.S., as indicated in this range map is from the Kaufman Field Guide to Butterflies of North America.

For a long time, Viceroys have been described as mimicking Monarchs, benefiting from looking like Monarchs, who are toxic to most birds. It has now been established that Viceroys have their own, different kind of, toxicity.

They don’t need to be misidentified by insect-eating birds to be avoided. And Monarchs likely benefit from being misidentified as Viceroys.

So this week I am celebrating the Viceroy as a full equal to the Monarch, not subordinate and not dependent. It deserves to be highlighted for itself.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.