-

Ring-necked Pheasant: Territorial Crowing

Leonard Weber

May 27, 2024

Native to Asia, the Ring-necked Pheasant was introduced into the United States in the late 1800s and became a popular game species in many parts of the country.

The male (usually called cock) is distinctive, with a red “face” and a long tail.

Photo from Eliza Howell Park, courtesy of Danielle Hawkins This is the third straight May that the loud two-syllable crow of the cock pheasant can be heard quite frequently in Eliza Howell Park in Detroit. This crowing functions as a territorial claim, communicating with potential mates and warning away other males.

The pheasant is a bird at home in tall grasses and brushy woods, heard much more frequenly than seen. Each time I have seen a male, the observation has been short. They walk or run, rarely fly, but are able to disappear quickly into cover.

The much less colorful females are even more difficult to spot, and I have not yet seen any females here.

Recently, this year’s calling male appeared while Danielle Hawkins had her camera with her. This photo was enlarged to emphasize the red, blue, and white of the head and neck.

Photo courtesy of

Danielle HawkinsThe wild pheasant population in Michigan probably peaked in the 1960s and has been in slow decline since. In recent decades, a bird long associated with grasslands and prairies and agricultural fields has found a home in Detroit, a city where a declining human population has resulted in more open areas with tall grasses and other plants. Pheasants are now doing very well here.

The sections of Eliza Howell Park devoted to perennial wildflowers and grasses provide possible nesting sites for this ground nesting species.

Photo courtesy of Danielle Hawkins Another birding enthusiast visiting the park recently reported seeing the male pheasant chase away a Wild Turkey, another ground nesting species.

This may be the year that Ring-necked Pheasant gets added to the list of “birds that are known or probable Eliza Howell Park breeding species.”

-

Ruby-throated Hummingbird Nest: Short-lived Excitement

Leonard Weber

May 19, 2024

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds nest in Eliza Howell Park, probably every year, but finding a hummingbird nest is not easy and happens rarely.

Earlier this month of May, as we were preparing for the next session of the BIRDS NESTING field course, one of my colleagues spotted a female hummingbird in an American Sycamore tree. It flew away, but returned to the same spot almost immediately. There was not much to see yet, but we were seeing the beginning of hummingbird nest. It was being constructed on a small limb about 15 feet high, not hidden by leaves and close to the path, an excellent location for observation.

The next day (Day 2), she was working energetically on the nest during each observation.

Female Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Photo courtesy of Margaret Weber A nest is made of small pieces of plant material, including down, and is bound together by spider webs. The outside is coated with flakes of lichen.

Photo courtesy of Margaret Weber I used the word “she” above because the male Ruby-throated Hummingbird does not participate in making the nest (or in incubation or in feeding the hatchlings); everything is done by the female alone. The male can often be seen perched in a tree, moving from one lookout spot to another, keeping watch over his territory.

The next photo is from a previous year.

Male Ruby-throated Hummingbird, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber On Day 3, the nesting course participants (and a few others) had an opportunity to watch as the hummingbird continued nest construction. The nest was larger and more solid looking, but still quite small.

Photo courtesy of Danielle Hawkins Based on field guides that I had consulted, I expected the nest to be complete after about 5 or 6 days. My personal experience was limited to one nest located in the park some years ago. I anticipated that the finished nest would look like this.

Eliza Howell Park, 2016.

Photo courtesy of Margaret WeberBecause I thought the nest was not nearly at the “move in” stage, I was surprised to be informed on Day 4 by another colleague that the hummingbird had been on the nest that morning and had, in fact, already laid an egg.

The report also included the news that the egg was lost, fallen from the nest.

He later sent images.

Photo courtesy of Kevin Murphy

Photo courtesy of Kevin Murphy Shortly after the egg fell from the nest, the bird flew away. Hummingbirds normally have two eggs per clutch, so the question was whether the mother would return, lay another egg, and continue with this nest.

The answer turned out to be no. She was last seen on Day 4. This is now Day 11. To my knowledge, no one has seen her at the nest or in the Sycamore tree in a week.

The tiny empty nest is a reminder that nesting attempts are quite often unsuccessful.

Nest on Day 4,

photo courtesy of Margaret WeberRuby-throated Hummingbirds often have two broods a year — making a different nest for each. My expectation is that this female will start over soon, but the chances are very good that we will not know what happens next. Locating another nest this year is unlikely.

It was both a great and a sad nest-watching experience: exciting to watch a hummingbird at work on a nest and disappointing that the observations were so limited.

It was one of nature’s short-lived gifts.

-

Red-winged Blackbirds: Now Nesting

Leonard Weber

May 12, 2024

The Red-winged Blackbird is a common and well-known bird in southern Michigan that is usually found near water. It arrives annually in Eliza Howell Park in March. It is a short-distance migrant, spending the winter as far north as Ohio.

The males arrive first and establish their breeding territories.

Male Red-winged Blackbird.

Photo courtesy of Margaret WeberThe females, which do not have the red patches and are not as well known, arrive a couple weeks later.

Female Red-winged Blackbird.

Photo courtesy of Margaret WeberEarly May seems to be the peak of their nesting time here.

This year, perhaps because there is more standing water in the park, the numbers appear to be up and their nests are easier to find.

Nest # 1 was made in a shrub growing in a wetland, about 2 feet above a foot of water.

Having watched, from a distance, the construction of the nest and having a sense of when the female had probably started laying eggs, I timed my visit for a close-up look for a time when the clutch was not yet complete and she was not yet incubating — and when she was not visible around the nest. This is a less disruptive time.

The nest contained two eggs (a typical full clutch is 4).

Nest # 2 was made in a different park of the park, near the meadow pond, and was only about a foot above a couple of inches of standing water.

Nest is between the viewer

and the pond.After confirming that the female was not on the nest, I also approached this nest for a quick look and a couple photos. The nest had 3 eggs.

The first picture was taken in the sunshine. Then I shaded the nest by blocking the sun with my body. Note how the color of the eggs, the same three eggs, appears so different as a result.

I did not approach a third nest that I spotted because the female was always near the nest and would have been quite disturbed by my presence.

Almost all of us who have gotten close to a Red-winged Blackbird nest, intentionally or not, have had the experience of being visited by a male flying right over our heads and calling loudly, telling us to leave immediately. I tend to pay more attention to the female blackbird than to the male in deciding whether / when to check a nest, but this behavior of the male does serve as a good reminder that it important to be careful.

Photo courtesy of Margaret Weber A few days later, my colleagues and I noticed that the female was not on Nest # 2 when it should have been incubation time. And the male was not protecting the immediate area. So we walked out to take a look. The nest was empty, with one damaged egg floating in the water.

It’s not possible to know exactly what happened, but a reasonable guess is that one of many different bird egg predators (which include some mammals, some birds, and some snakes) consumed the eggs.

Making a study of the nesting birds of Eliza Howell Park in recent years has taught me how often nests are unsuccessful, for a variety of different reasons.

Bird nesting behavior is fascinating, but it is definitely not easy being a bird!

-

Blue-gray Gnatcatcher: Tiny Bird, Fascinating Nest

Leonard Weber

May 6, 2024

One of my May bird-watching goals each year in Eliza Howell Park is observing nesting activities of Blue-gray Gnatcatchers. For each of the past 13 years, this goal has been achieved. Two nests in process have already been located in 2024.

The Blue-gray Gnatcatcher is a very small bird that is almost constantly in motion. A few begin arriving in the park in late April every year, after having spent the winter, perhaps, somewhere in Central America.

Photo courtesy of Margaret Weber Blue-gray Gnatcatchers are insect eaters, though they don’t seem to focus specifically on gnats. They forage in foliage and on limbs, sometimes flicking their white-edged tail.

Photo courtesy of Margaret Weber Within days of arriving here, they begin nest building, a process that can take up to two weeks. The female and male work together, using tiny pieces of plant fibers, hairs, bark, catkins, fine grasses, and similar material, all bound together and attached to the support limb by spider webs. The nest is considerably taller than wide, when complete. and is quite flexible. The inside of the cup is less than 2 inches in diameter, just big enough to hold the typical 4 eggs / young of these small birds.

In the following photo sequence, a male is bringing a female a piece of nesting material (it looks like it might be bark) and heading back for more.

Three photos courtesy of

Margaret WeberThe completed nest is “decorated” on the outside with lichen flakes, helping to camouflage a nest placed on a tree limb that often has lichen on it.

The next photo is of a finished nest. This is a close-up view of the nest on a small limb; the nest is not as big as it may seem here.

Photo by author Both sexes incubate the eggs and both feed the young, just as they both build the nest. The nestlings have a diet of insects, either in adult or larvae form.

Photo courtesy of Kevin Murphy When the young are a little larger, the feeding parent no longer needs to reach into the nest: they are met above the rim.

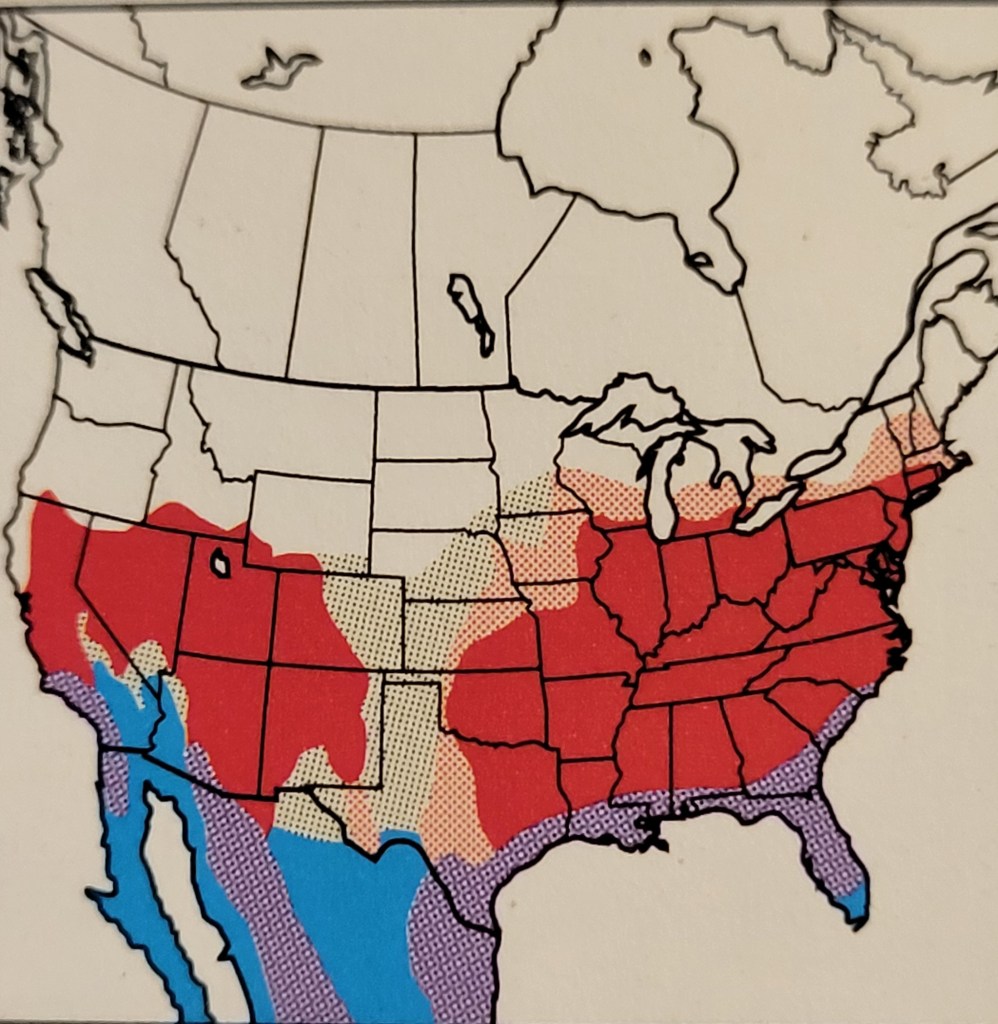

Photo courtesy of Kevin Murphy Though Blue-gray Gnatcatchers are regular breeding-season residents of Eliza Howell Park, they are not abundant overall and are not recognized by many people. They have been expanding northward in recent decades, but they remain much more a southern species. Southern Michigan is as far north as they breed. (Map key: red = breeding season; blue = winter grounds; purple = present all seasons.)

Map from

Kaufman Field Guide to Birds of North AmericaIt takes time and careful watching every year to find these active little insectavores in the process of nesting, but it is immensely satisfying. Perhaps most satisfying of all is to be able to provide an opportunity for others to watch and enjoy.

Photo courtesy of Kevin Murphy -

Red Admiral: Why So Abundant in April This Year?

Leonard Weber

April 28, 2024

Nature is usually predictable in terms of the annual sequence — what animals are visible and active at specific times of the year.

Every once in a while, there is something unusual enough to raise the question: “Why is this happening?” This year, there has been an unusually large number of Red Admirals in Eliza Howell Park in April.

April 9 Over the years, Red Admiral has been a regular in the park, one of the butterfly species seen many times from spring to fall. In the heart of the summer, they can be seen visiting flowers in bloom. July is a good time to get good views of them nectaring.

July 20,2022

July 18, 2021 Red Admirals survive the winter as adults in a state of diapause (similar to hibernation). They cannot survive very cold temperatures, however; those that spend the summer in northern climates migrate south for the winter and return in the spring.

Most of the reports indicate, though, that they can survive some freezing weather, as long as it is not too intense.

The Red Admirals in southern Michigan have long been thought to be migrants. The large number present this early in the year leads me to wonder whether, because of more mild winters, an increased number of Red Admirals are now spending the winter here.

Several photos from April, 2024 There are fewer flowers in bloom in the park in April than in the summer, but the Red Admirals do well without nectar. They are often seen on the ground, getting moisture and minerals. Their preferred foods are reported to be tree sap, animal droppings, and rotting fruit.

April 22, 2024 Red Amirals fly fast and are not easy to recognize while in flight. When they stop, they are very identifiable, especially when they have their wings open.

This April, their numbers have far exceeded that of all other butterfly species combined — a question-raising phenomenon!

-

Bloodroot: A Spring Ephemeral at Eliza Howell Park

Kathleen Garrett

April 20, 2024

Like other woodland spring ephemerals, Bloodroot appears in the woods in early spring, before

the trees leaf out, and lasts only a couple of weeks, and sometimes less.At Eliza Howell Park, there is a group of Bloodroot in the woods just off the side of the road loop, but there may be more in other locations in the woods. They seem to prefer a hillside.

In spring, usually April, a single, rolled leaf emerges from leaf litter, holding a single flower bud.

As the temperature warms, the leaf unfurls and an eight petaled, white flower with a yellow center, about 2 inches across, blossoms. These flowers close at night and/or in the shade, and open again with warmth. The flower will die in about two weeks, but the puzzle-piece shaped leaf will continue to grow, (up to 9 inches across).

Bloodroot is named after the red or orange juice that oozes out when its stem or root is broken. Several sources list a number of historical and/or Native American uses for this juice, among them dye, insect repellent, and as a treatment for inflammation, infections, and cough.

Photo courtesy of Leonard Weber Bloodroot is native to Eastern North America and spreads via rhizomes or small bulbs below ground.

Bloodroot is a “generalist,” meaning that it can also be pollinated by many kinds of insects. This increases the chances of survival and propagation. If pollinated, seed pods appear after the flowering is over. These seed pods hold about 30 seeds. Each seed has an organ,

called an elaiosome, that is attractive to ants. Ants carry these treats back to their nests. After

they eat the elaiosome, but not the seed, the ants carry the not so delicious seeds to their trash

dump, and so the seeds are planted among the debris. It’s a clever, if not

glamorous, beginning to a beautiful, brief flower.

The season for Bloodroot is brief, so don’t put off going to the woods. Bloodroot is just one of the several spring ephemerals at Eliza Howell Park. If you miss them, you may never know they were there. They emerge, bloom, and die back quickly, disappearing into the forest floor until next spring.

-

An April Morning Walk: Toads, Trees, Flowers, Birds

Leonard Weber

April 15, 2024

It was a warm, sunny mid-April morning today, one of those days when it is evident that spring is progressing rapidly.

Mating time for American Toads lasts just a few days. During this time, males call loudly in the meadow pond at any time during the day.

Toad Breeding Pond This was the first day I heard them this year. They can typically be expected to gather in the pond after a warm nighttime rain (about 50 degrees or more). The last rain, about 3 days ago, might have initiated this year’s gathering.

These photos are from a previous April.

AmericanToad, photo

courtesy of Margaret Weber

Photo courtesy of Margaret Weber Eastern Cottonwood trees flower in April, and the flowers led me to stop – rather, to stop twice – on this morning’s walk. It required two stops because cottonwood trees are either male or female, with different flowers.

Flowers on a male cottonwood tree

Flowers on female cottonwood tree Only the female tree develops the seeds (the “cotton”), of course.

Another tree flowering on this April day is Eastern Redbud. The flowers appear along the branches well before there is any sign of leaves.

Eastern Redbud

Eastern Redbud (with white-looking aspen branches in the background) Bloodroot is a well-liked spring wildflower that grows only in limited locations in Eliza Howell Park. Last fall, the reconstruction of the park road resulted in digging up much of the ground in the location where the flower could be found most reliably.

Bloodroot, photo from the past This morning was my first search for an indication that some had survived here. I found just a couple leaves – so far. The flowers might not be plentiful this year, but not all were lost.

An emerging Bloodroot leaf This was also the first day that I noted Tree Swallows in the park this year, birds that have recently arrived back in Michigan from their wintering grounds (near the Gulf coast). A few nest the park, in a cavity in a tree.

Tree Swallow, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber April is also the month for seeking the hard-to-find Killdeer nest. They lay eggs a “minimalist nest” on the ground, very difficult to locate even though right out in the open.

The best time to look is before the clutch of (usually 4) eggs is complete; the adult is not yet on the nest incubating and will not be as disturbed by the search.

The nest photographed this morning has two eggs (so far).

Killdeer nest

Killdeer nest, a closer look

Killdeer, photo courtesy

of Margaret WeberThere is much more that could be said about each of these stops, and there were a number of other observations this morning as well. Perhaps this provides a sense of an April “walk in the park.” I look forward to returning very soon!

-

Spring Beauty: The Ephemeral Wildflower Season Begins

Leonard Weber

April 9, 2024

The early woodland wildflowers are often referred to as “ephemerals” because they bloom for only a short time in early spring. They take advantage of the few weeks before the large trees have leafed out and shaded the forest floor where they live.

On April 9 this year, a warm and mostly sunny day, Spring Beauty, the earliest of the ephemerals, was easily discernible to anyone looking carefully (studying the ground!) along the path in the Eliza Howell Park woodland. It is a diminutive species (about 2 inches tall), and I think, appropriately named.

Spring Beauty is sometimes more pink, sonetimes more white.

I find myself drawn to the brighter ones

and to the ones that are attracting insects.

Ant on Spring Beauty

Spring Azure butterfly nectaring

on Spring BeautySpring Azure is one of the very earliest butterflies to appear each spring. Its blue (azure) color shows when the wings are open.

There was just a hint on the April 9 afternoon walk of the other ephemerals that will be appearing in greater numbers soon.

Yellow Trout Lily

White Trout Lily

White Trout Lily with (what appears to be) Cellophane Bees Trout Lily is a little taller than Spring Beauty, as is another flower that will be in greater numbers soon – Cut-leaved Toothwort.

Cut-leaved Toothwort

Cut-leaved Toothwort

with unidentified insectThe above are just four of the flowers that are likely to be present on Saturday, April 27, during an afternoon Spring Ephemerals nature walk in Eliza Howell Park, sponsored by Detroit Bird Alliance and led by Kathleen Garrett.

-

Nesting Mourning Doves: No Insects Needed to Feed Young

Leonard Weber

March 31, 2024

It is not unusual that the first (non-raptor) bird species that can be observed nest building in the spring in Eliza Howell Park is the Mourning Dove.

Since March 21, I have been checking regularly on one of their nests. We were in the midst of a cold spell when I located it that day; 4 inches of snow fell the following day.

Through the cold and snow, the nest has been attended day and night (female and male share the duty of keeping the eggs warm, the female taking the night and the male the day). I don’t know when the eggs were laid, but the end of the usual 14-day incubation period may be arriving soon.

Mourning Dove on nest, March 24 Mourning Doves are common year-round birds in the park and several pairs nest here each year. Though they are common, their nesting-related behaviors are quite uncommon.

They usually start their breeding season singing (“cooing”) by the end of February and the first ones start nesting in March, several weeks before many of the other breeding birds of Eliza Howell even return from their wintering grounds.

In the act of “cooing,”

February 22There are other ways in which Mourning Dove nesting behavior is atypical.

They put together a flimsy nest of twigs and grass, a nest without an inner cup, in about 2-3 days. This compares to about a week for many other species. The female stays on the chosen limb as the male brings each piece to her, steps on her back, and presents it to her when she turns her head. She then tucks it under and/or around her while he immediately gets the next piece. It is a very quick construction process, fascinating to watch.

The nest shape and construction are partially visible in the next photo.

March 28, photo courtesy

of Margaret WeberMourning Doves typically lay just two eggs (half as many as most song bird species). They have 2 or more broods each year, so they are able to keep their numbers up despite the small brood size

The number of eggs per brood is directly related to the method of feeding the young.

While other song bird species that nest here feed insects to their hatchlings, birds in pigeon family (pigeons and doves) have the capacity to produce “crop milk” or “pigeon milk” to feed the babies.

Pigeon milk is a semi-solid substance (described sometimes as being like cottage cheese). It is high in protein and fat. The young are not able to digest the Mourning Dove regular seed diet in the first days after hatching. Both females and males produce the milk and feed the young, but even between the two of them there is not enough milk for more than two young at a time.

Photo courtesy of Margaret Weber The ability to produce pigeon milk makes early nesting possible. They do not need to wait for an increase in insect prey for feeding the young, as other birds do.

It’s not easy for observers to know when the eggs hatch. There will be no frequent visits to the nest as the parents bring insect food. Rather, the parent will continue to keep the chicks warm, feeding them “milk” without needing to leave the nest.

If all goes well and if my visits are timed right, perhaps I will be able obseve the young several days after they hatch, when they have grown enough that the parents are transitioning in feedings from milk to seeds.

Photo courtesy of

Margaret Weber -

Focus on Tree Buds

Leonard Weber

March 26, 2024

The buds have been present at the ends of the tree branches since last fall but have been dormant for months. Now, dormancy has ended and the buds are growing.

This is a great time to take a careful look and to note how the buds of different species vary. On my most recent walk, I stopped for a number of photos.

Sugar Maple

American Beech

American Sycamore

Wild Black Cherry

Hawthorn

Chinkapin Oak

Norway Maple

Shagbark Hickory The deciduous trees here are still bare, and it will be a while before they are all green again. But these attractive and growing buds are communicating very clearly that the process is definitely underway.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.