-

BIRDS NESTING: A Spring Field Course

Leonard Weber

March 20, 2024

One of the highlights of nature observation in Eliza Howell Park each year is bird nesting season. There are some 30 species that regularly nest in the park, and in any one year, patient and frequent observation, guided by knowledge of species-specific nesting practices, can result in the opportunity to study many of them.

This year, in a program stretching from April 27 until early June, in weekly Saturday mornings in Eliza Howell Park, we will be providing a a 6-week course focused on getting to know more about the nesting behaviors of a variety of bird species. This time is the peak of nesting activity.

NOTE: All photos below were taken in Eliza Howell Park.

Some species nest in tree cavities, excavating new holes or using pre-existing ones.

Red-bellied Woodpecker, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber

Eastern Bluebird, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber

Black-capped Chickadee, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber Some species build nests on tree limbs.

American Robin,

photo by author

Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, photo courtesy of Kevin Murphy Some species make nests on the ground.

Killdeer nest, photo by author Some species fit nests in among the branches of shrubs or small trees.

Northern Cardinal, photo by author Some species weave hanging nests in trees.

Orchard Oriole, photo courtesy of Kevin Murphy

Baltimore Oriole, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber Some species build nests on protected surfaces of human-made structures.

Barn Swallow, photo by author We will also be considering the usual dates of nest making for different species, the types of trees selected by tree-nesting birds, the roles of females and males in incubation and care of hatchlings, the identification of altricial and precocial species, etc.

In advance of each session, colleagues Mara Crawford and Kathleen Garrett will join me in mapping the route so that we can make best use of group time.

The field course is sponsored by Detroit Bird Alliance. For more details, please check Detroit Bird Alliance events.

I recently watched a pair of Mourning Doves making a nest in a,spruce tree. Nesting season is starting!

-

First Garter Snake of the Year

Leonard Weber

March 16, 2024

It is always sunny when I encounter the first Eastern Garter Snake of the year in Detroit’s Eliza Howell Park.

We have reached the time this cold-blooded species is starting to seek the warmth of the sun after months of “brumation.” This year’s first sighting was on March 15, as I walked off-path on grass and fallen leaves.

Eastern Garter Snake,

March 15, 2024Now is a good time for Garter Snake watching because they are not as quick to disappear: it seens like they just want to bask in the sunshine.

March 15, 2024 The date of the first sighting varies a little, the differences probably at least as much the result of where I happen to walk as when they first come out.

In recent years, my first-of-the-year sightings have been:

2023 — April 7

2022 — April 9

2021 — March 11

2020 — March 23

2019 — April 2

March 23, 2020 In March and April, it is often possible to observe carefully — to see the magnificent tongue and to note the scales in a way that is not possible in their more active season.

April 13, 2023

March 29, 2020 Eastern Garter Snake, a non-venimous species, is by far the most common snake in Eliza Howell Park. This fact and the close-up views on spring nature walks have inspired me to find out more about its life. Among other things, I have learned that

* Garter snakes are one of a minority of snakes (about 30 %) that give birth to live young instead of laying eggs (the other 70 %). The multiple young are not cared for by adults but need to find food on their own from day one.

* They can be active both in daytime and at night and are full carnivores (eating only animal matter); their prey consists of worms, slugs, insects, snails, amphibians, crayfish, bird eggs, etc.

* They spend the winter in groups underground (e g., in crayfish or mammal burrows) or in other protected locations. Their winter time of inactivity and torpor is called “brumation” in recognition of the differences in the way cold-blooded reptiles survive winter from the “hibernation” of warm-blooded mammals.

When they first emerge in the spring, there are often two or several together.

April 2, 2019 The next days and weeks, when the sun is shining, are the best time of the year to look for Eatern Garter Snakes,

April 9, 2022 to watch them, and, if one wishes, to photograph them.

-

The 11 Birds of March: Migrants Start to Return

Leonard Weber

March 8, 2024

When March arrives in Eliza Howell Park, it is time to expect the return of the first of the bird species that migrated south for the winter.

Over the years it has become clear: the earliest returning migrants, 11 of them, very likely to show up in March.

Here are the March 11.

1. Wood Duck

First observed in EHP in the previous 10 years (2014 – 2023):

In March – 9 times; in February – once

In 2024 – February 28

Wood Duck male and female, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber 2. Common Grackle

In 2014 – 2023: March – 9 times; February – once.

In 2024: March 1.

Common Grackle, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber 3. Red-winged Blackbird

In 2014 – 2023: March – 7 times; February – 3 times.

In 2024: February 23

Red-winged Blackbird male and female, photos courtesy of Margaret Weber 4. Brown-headed Cowbird

In 2014 – 2023: March – 10 times

In 2024: March 3

Brown-headed Cowbird male and female, photos courtesy of Margaret Weber 5. Killdeer

In 2014 – 2023: March – 8 times; February – once; April- once

In 2024: February 26

Killdeer, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber 6. Eastern Bluebird

In 2014 – 2023: March – 9 times; February – once

In 2024 – February 22

Eastern Bluebird male and female, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber 7. Song Sparrow

In 2014 – 2023: March – 8 times; February – twice

In 2024 – March 6

Song Sparrow, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber The above seven species are the ones that I have observed so far this year. Most of them have arrived a little earlier than usual, perhaps because this has been a warm winter.

The March arrivals are short-distance migrants, spending the winter only hundreds of miles away, rather than thousands. The ones that will arrive in April and May go longer distances (more about them later).

8. Turkey Vulture

In 2014 – 2023: March – 10 times

In 2024: Not yet observed

Turkey Vulture, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber The Turkey Vulture is the first one on this list that doesn’t nest in the park* (at least, I don’t think that it does). It is a scavenger and can often be seen from about the middle of March to October, flying over as it seeks food.

(*Note: Cowbirds don’t make their own nests, but lay eggs in the nests of other species.)

9.Great Blue Heron

In 2014 – 2023: March – 8 times; April – twice.

In 2024: Not yet observed.

Great Blue Heron, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber The Great Blue Heron also visits the park while foraging for food, but does not nest here. A colony nesting species, the ones seen here might nest in a the rookery a few miles downstream along the Rouge River.

10. Eastern Phoebe

In 2014 – 2023: March – 7 times; April- 3 times.

In 2024: Not yet observed.

Eastern Phoebe, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber 11. Northern Flicker

In 2014 – 2023: March – 7 times; April – 3 times.

In 2024: Not yet observed.

Northern Flicker, photo courtesy of Margaret Weber Sometimes, one or more of these 11 species is seen in southern Michigan in the winter, including in Eliza Howell Park; we are near the northern edge of their winter range. But that doesn’t happen very often. I do not expect to see them before March and I do expect to see them in March.

There is a very real way in which a new year starts about the beginning of March.

-

Catkins on Quaking Aspens: Observation-based Learning

Leonard Weber

March 4, 2024

The Aspen flower buds in Eliza Howell Park are fuzzy in early March. Over the next weeks, the flowers will develop into hanging clusters of seeds (catkins).

March 1, 2024

March 4, 2024 During the winter of 2022 – 2023, one tree in the small grove of Quaking Aspen in the park was blown almost entirely down, but it continues to live. This is the second year it is providing an opportunity to get up-close views of the buds, flowers, and seeds that are usually much too high to study.

Quaking Aspen in March As I check the progress of the catkins, I will use last year’s photos as a guide to what to expect and for comparison.

March 21, 2023

April 2, 2023

April 7, 2023

April 13, 2023

May 10, 2023 Aspen trees are dioecious; each tree has only female or male flowers and pollination means that pollen from male trees need to reach female trees. That reality, combined with the likelihood that all the trees in a particular Aspen grove are from the same root system (are really just one tree and, therefore, one sex) leads one to wonder how pollination occurs in a place like Eliza Howell where there are not multiple groves.

Quaking Aspens are normally wind pollinated, I have learned, and the pollen can travel quite a long distance. Wind pollination also helps to explain the paucity of insects visiting the flowers during my many visits last spring.

I may well have additional questions as I watch the catkins develop this year.

March 4, 2024 The discovery of a fallen live tree has provided the opportunity to observe more closely. Closer observations have led to questions to be researched. The answers to these questions lead one back for further observations to improve understanding.

This is typical, it seems, of the way nature-walk learning occurs.

-

The Elusive Pileated Woodpecker: Signs of Its Presence

Leonard Weber

February 23, 2024

A little over 15 months ago (November 14, 2022), I reported my first sighting of a Pileated Woodpecker in Eliza Howell Park in Detroit. Since then, I have seen one in the park three other times, but just once in the last 12 months (on January 10, 2024).

Since the January sighting, I have spent hours searching for this magnificent bird. (Note: this photo was taken at another location, not the park.)

Pileated Woodpecker, photo

courtesy of Margaret WeberThe bird has eluded me, but the search has provided significant evidence of recent presence.

Pileated Woodpeckers eat many Carpenter Ants (estimated to be about 50% of their total diet), digging deeply into dead wood to find them. Carpenter Ants are social insects, with large numbers of them living together in colonies. The ants make tunnels in dead wood and Pileated Woodpeckers dig deep gouges in dead trees and logs to get to them, lapping up Carpenter Ants by the dozens (perhaps by the hundreds) with their long sticky tongues.

The bird in the photo above is excavating a dead standing tree. In the next photo, from a different location, one is working on a log.

Photo courtesy of Margaret Weber Recently excavated large gouges in trees or in logs are signs that a Pileated Woodpecker was here not long ago. The next three photos were taken this February in Eliza Howell Park.

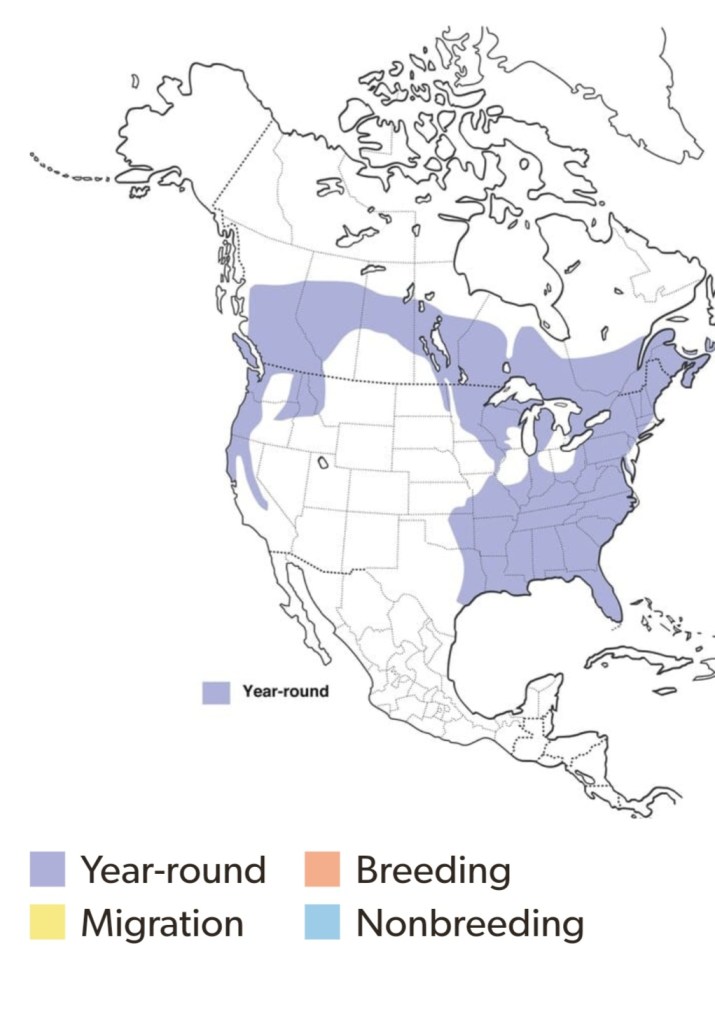

In addition to more opportunity for the exciting experience of watching Pileated Woodpeckers working for their dinner, the on-going presence of Pileated Woodpeckers in Eliza Howell Park would mean that the species has moved into Detroit, an expansion of its range.

The part of Michigan (southeast Michigan) that is not part of the Pileated’s regular range includes Detroit.

Map from Cornell

Lab Of OrnithologyAt this point, we have both types of evidence of its (recent) presence: occasional visual sightings and several examples of ant-seeking excavations. What is not known yet is whether there is just one individual or a pair and whether it/they have moved in or are just visiting.

So the search continues!

Kathleen Garrett called

my attention to this treeI think it likely that these two holes in a dead Black Cherry tree were made by a Pileated Woodpecker. If so, perhaps it is making fun of the searchers!

-

Birds Are Singing, Winter Is Waning

Leonard Weber

February 11, 2024

We have now reached the point in winter when there are clear signs that bird behavior is beginning to change from non-breeding to breeding season.

Three Eliza Howell Park species signal the approaching breeding season by singing songs that haven’t been heard regularly here for months: Tufted Titmouse, Northern Cardinal, and Mourning Dove.

Tufted Titmouse, photo courtesy

of Margaret WeberIn late winter, Tufted Titmouse begins to establish nesting territories and sing their loud “peter, peter, peter” song (as it has often been described) to announce the borders.

This year, I heard the song for the first time on February 1. Tufted Titmouse is a small and not-very -brightly-colored year-round bird; the song is a welcome reminder that it is planning to nest here.

Tufted Titmouse, photo courtesy

of Margaret WeberEvery year, I expect to hear the first singing of the Northern Cardinal on a sunny day in February. Starting in 2020, I have made note of the date of that first singing:

2020 = February 12

2021 = February 17

2022 = February 8

2023 = February 11

2024= February 6

Male Cardinal, photo courtesy

of Margaret Weber

Female Cardinal, photo courtesy

of Margaret WeberThe commencement of Cardinal singing can also be taken as the start of their annual process of selecting and defending breeding territories.

The third species whose late winter singing is eagerly anticipated is Mourning Dove. After spending the winter in flocks, they are now (or will very soon be) forming pairs.

Mourning Dove, photo courtesy

of Margaret WeberThe first “cooing” of the year is an announcement that these early nesters will be turning their attention to selecting a site for their first brood soon. I have not heard it yet this year, but expect to before the end of February.

Mouring Doves, photo courtesy

of Margaret WeberMany of the birds that breed in Eliza Howell Park are summer residents. Some of them don’t arrive until May and begin to build nests almost immediately. We don’t have the opportunity to watch their change from winter behavior to breeding season behavior.

Thanks to a significant number of breeders that are year-round residents, however, we can observe the whole seasonal change process. For some species, the singing that starts in February is the first indication that winter is waning and that breeding season is coming.

-

Amber Jelly: A Winter Mushroom

Leonard Weber

February 1, 2024

I should know better after all these years, but every winter I am a little surprised to find mushrooms thriving in January and February here in Detroit.

Recently, my attention has been on a species known as Amber Jelly (also known as Jelly Roll, Amber Jelly Fungus, and Brown Witch’s Butter).

Amber Jelly is a small mushroom that is found, frequently in clusters, on dead or dying limbs and twigs, especially of oak trees. Following snow or ice events, one can often find it by looking closely at newly fallen dead branches.

It is a small mushroom. The individual caps are usually less than inch across. It is a decomposer, contributing to the rotting of the dead wood.

The “amber” part of the name seems a little misleading. It is more brown or purplish. Perhaps it would look different seen with sunshine behind it, but all of my photos are from cloudy days.

The “jelly” part of the name rings more true. It looks and feels somewhat like jelly, soft and flexible, but not squishy.

It is often possible to spot Amber Jelly on some of the small branches that are still attached on oak trees, limbs that have recently died but have not yet fallen.

One of the other attractions found on trees and tree limbs at this time of the year is lichen. The combination of lichen and Amber Jelly can be very attractive.

When all the world seems dark and gray and we might be getting eager for winter to end, it can be very satisfying to stop and examine small limbs on the ground under oak trees.

Nature’s wonders are not all dormant!

-

Box Elder: Samaras in Winter

Leonard Weber

January 30, 2024

One of the trees that is easy to recognize during winter walks in Eliza Howell is the Box Elder. To be more precise, the female Box Elder tree with low branches is easy to recognize.

The winged fruit/seeds (samaras) hang on till late winter.

Box Elder is a type of maple, as the seeds indicate, but the leaves are different from typical maples. The compound leaves, with three to five leaflets, are now long fallen; our full attention is drawn to the seeds.

Box Elder is dioecious, a species with separate female and male trees. Females and males have different types of flowers in the spring (about the time that the leaves begin to grow) and, of course, only females produce the seeds.

Box Elder is known as a tree that often does not grow straight and has brittle limbs that frequently break.

One of the reasons the tree is so noticeable in winter is that seed-bearing branches are sometimes close to the ground on bent or broken branches.

It is native to this part of North America and grows in different environments and soils. A good place to look for it, however, is near a river or in some other wet area. It is easiest to find in the park in an area that frequently floods.

The bark is commonly the focus when getting to know trees better in winter. In the case of Box Elder, however, the clusters of seeds persisting into late winter definitely distract my attention from the bark.

I usually get to know a tree species first in the growing season, and that recognition is the starting point for additional observations in winter.

In the case of Box Elder, the opposite is true. This January, I have been making note of several samara-laden trees. These looks will, I hope, remind me to stop and examine the flowers and leaves more carefully in spring.

I am putting Box Elder on my spring agenda.

-

Watching the River Freeze

Leonard Weber

January 20, 2024

The Rouge River flows through Eliza Howell Park, and one of my annual winter questions is when (or whether) it will freeze over.

There is always a current and it takes a sustained period of very cold weather to freeze the whole surface. I always observe at the same location, standing on the footbridge and facing upstream.

This has been a warm winter and, until quite recently, the surface was almost entirely without ice. Here are two views from earlier this month.

January 2, 2024

January 8, 2024 A cold spell began about a week ago. The last day the temperature was above 32 F was January 13. On January 14, the high was about 19 degrees with a low of about 0.

The next day, the view had begun to change.

January 15, 2024 The ice was beginning to form near the river edges, where the current is less strong.

The next day was even colder, with a high of about 12 and a low slightly below zero. The effect was obvious (and was made more evident by a light snowfall).

January 16, 2024 A close-up look at a section of the photo indicates how the ice surface expands, stretching out from the sides toward the center of the river.

January 16, 2024 Based on past observations, I have come to expect that the river surface will freeze over at this location when there are several consecutive days when the temperature does not get as high as 20 degrees.

On January 16, the high was about 16 degrees.

January 17, 2024 There was no additional snow, so the ice in the center of the river is not easy to see. A closer view confirms that the ice now stretches from shore to shore.

January 17, 2024 It has remained cold and there have been a couple more small snowfalls. This is the most recent photo.

January 20, 2024 The ice is thin, and there remain spots elsewhere in the park where the river surface is not frozen. For the purpose of my year-to-year comparison, however, there has now been one Rouge River freeze this winter.

A thaw is in the forecast for the coming week and, with melted snow entering the river, the ice will likely break up quite quickly.

It remains to be seen whether this is the only river freeze this year.

The River Watcher

January 15, 2024

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.