-

Birds Forming Breeding Pairs: Winter Watching

Leonard Weber

January 15, 2024

Most of my bird watching in winter in Eliza Howell Park involves observations of the ways different species forage for food. I enjoy finding Downy Woodpeckers and White-breasted Nuthatches and Brown Creepers searching crevices of tree bark for insect larvae and eggs, and I try to spot Goldfinches and Tree Sparrows and Dark-eyed Juncos gleaning any remaining seeds in the wild flower fields.

When we reach the middle of winter, though, I start to watch for changes in behavior that indicate the approach of the breeding season.

Now is the time to start to watch for pair bonding.

Female Northern Cardinal,

photo courtesy of Margaret WeberCardinals tend to spend most of the winter in small flocks, but, in late winter, they form pairs and become territorial. The loud and distinctive whistling song that we hear frequently during spring and summer is absent in late fall and winter — until February. Their renewed singing in February is one clear indication that spring breeding season is coming.

(In the last four years, I heard the first-of-the-year Cardinal singing in Eliza Howell on Feb. 12, Feb. 17, Feb. 8, and Feb. 11.)

Male Northern Cardinal,

photo courtesy of Margaret WeberAnother year-round species that spends the winter in flocks (up to 15 individuals) is Mouring Dove. They forage for seeds on the ground. I usually see them when they fly up to perch in trees.

Mourning Dove,

photo courtesy of Margaret Weber

Mourning Doves,

photo courtesy of Margaret WeberMourning Doves also sometimes starts to call in February, the male sending out its “coo” message as an enticement to its (potential) mate. They start nesting very early in the year; based on my past records, I will look for nest building in the middle of March, before it is really spring.

Other Eliza Howell species that I often see pairing off in winter are Red-bellied Woodpecker …

Red- bellied Woodpecker,

photo courtesy of Margaret Weber.. and Downy Woodpecker.

Downy Woodpecker,

photo courtesy of Margaret WeberWhile most bird species form pairs that stay together during breeding season, they vary on the length of their bond.

Based on published reports, Mouring Dove, Downy Woodpecker, and Red-bellied Woodpecker usually pair for just one season, seeking a different mate the next year. Northern Cardinals normally partner for more than one.

Carolina Wren is another bird that is frequently seen (or at least heard) in winter in the park. They have the same mates year after year. And they are together all year, not just in breeding season; when I see one/hear one now in January, I usually see/hear two.

Carolina Wren,

photo courtesy of Kevin MurphyWe are now in the midst of winter, but I recently saw a pair of Red-bellied Woodpeckers together. It reminded me of how frequently pair bonding begins in the season of ice and snow.

-

Hackberry Trees

Kathleen Garrett

January 5, 2024

One of the easiest trees to identify by its bark is the hackberry. This fast-growing, native tree is abundant in the woods at Eliza Howell Park and can be quickly recognized by its raised ridge, often called “corky” bark. The ridges on the hackberry can be so pronounced they cast a shadow, as seen in this photo:

Also called sugarberry, nettletree, beaverwood, this tree has many uses, if not so much for human commercial use. The blueberry-sized fruit appears in late summer or early fall and changes color from an unripe green to a ripened orange-red or dark purple. Birds and small mammals eat the fruit and disperse the seeds. Humans can eat the seeds that are inside the flesh of the fruit, (apparently it tastes similar to figs), but the seeds are small and encased in a hard shell.

At Eliza Howell, the fruit is often hard to reach. Most of the hackberry trees grow quickly straight up, reaching for what sunlight they can find in the woods, fruiting finally in the higher branches well beyond our reach.

Cedar waxwings, Robins, Yellow-bellied sapsuckers, and Fox squirrels have no problem reaching the fruit, however.

For psyllids, an insect that looks alot like a small cicada, hackberry trees are essential. In the spring, psyllids deposit eggs on hackberry leaves, which causes abnormal growth of leaf tissue around individual eggs, called hackberry nipplegalls. This gall or growth offers protection to the larva while the larva eats the leaf and begins to mature. Once mature, the psyllid emerges from the gall and drops to the ground where it will molt and overwinter as an adult. Migrating songbirds rely on a plentiful supply of insects, psyllids included, to refuel. With its abundance of hackberry trees, Eliza Howell would be a great stopover site for songbirds passing through.

Butterflies are not often associated with trees, but there are several species of butterflies seen at Eliza Howell that rely on hackberry trees for incubation and food: Hackberry Emperor, Tawny Emperor, Mourning Cloak, and American Snout. The Tawny Emperor butterfly, for instance, lays its eggs in clusters on hackberry leaves in late July. The emerging caterpillars eat through the leaves and then scatter, each looking for a leaf to overwinter and then, in early summer, emerge as butterflies. Neither the psyllids nor the butterflies damage hackberry trees.

Tawny Emperor, photo courtesy of Leonard Weber One of the largest hackberry trees at Eliza Howell is about 8’ in circumference, which translates to about 60 years old. Interestingly, when young, hackberry bark is mostly smooth.

The beautiful and distinguishing ridges come with age, as if they are earned.

To learn more about identifying trees in winter at Eliza Howell Park, join the Detroit Bird Alliance Trees in Winter Walk on Saturday, Jan. 20 at 1 pm. You can register here.

-

Seasonal Bird Variation

Leonard Weber

January 2, 2024

This is the beginning of my 20th year of bird study in Eliza Howell Park in Detroit. I have recorded the birds seen here in every month of the past 19 years. This January is the 229 consecutive month, with a total of 2347 different bird-watching days so far.

The 20th year is good time, I think, to report on some of what I have been learning.

Over 19 years, the average number of bird species seen during the calendar year is 112. There are not 112 species present at any one time, of course. The average number of species seen in a month varies from a low of 19 in February to a high of 69 in May.

One important key to knowing birds is to recognize the migration (or non-migration) patterns of different species.

The species that are seen in southern Michigan can generally be divided into 4 different groups:

1. Present only in winter.

2. Present only in the breeding season (spring and summer).

3. Present briefly twice a year as they migrate through (north in the spring and south in the fall).

4. Present year-round.

Those species that spend the winter here are relatively small in number. They breed in the far north and our latitude is their southern wintering location.

—

1. Present only in winter. One example of a winter resident now found in Eliza Howell Park is the American Tree Sparrow.

American Tree Sparrow,

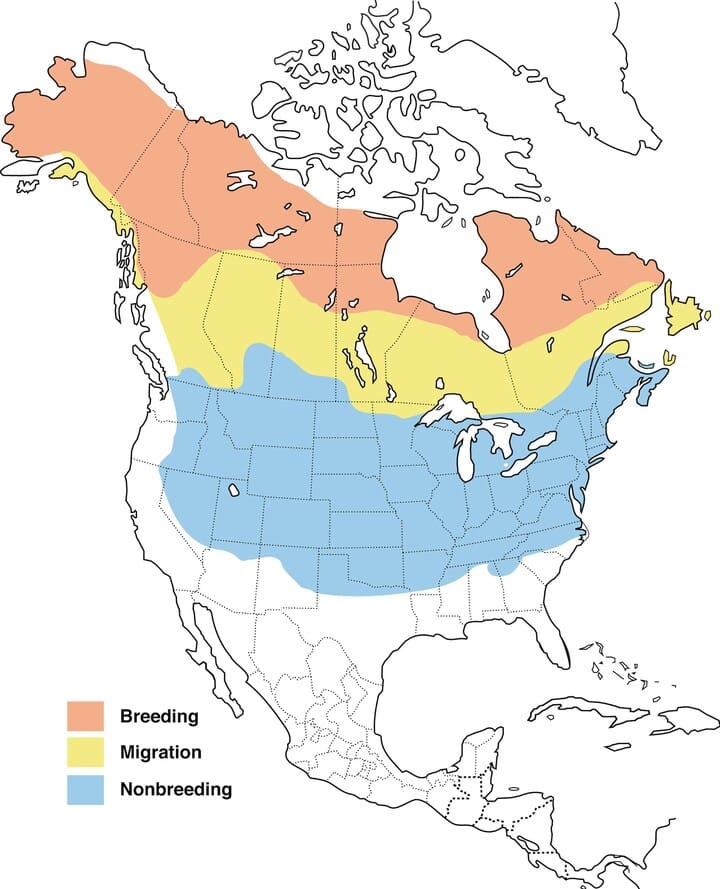

photo courtesy of Margaret WeberAs can be seen from the range map, found at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology species account, it has come a long way from its breeding territory to winter here.

Range of American Tree Sparrow 2. Present only in breeding season. Spring is such an exciting time for bird watching partly because many species that nest here return from their southern wintering grounds at this time and quickly turn to nest building.

One example is the Barn Swallow, which nests in the park every year.

Barn Swallow,

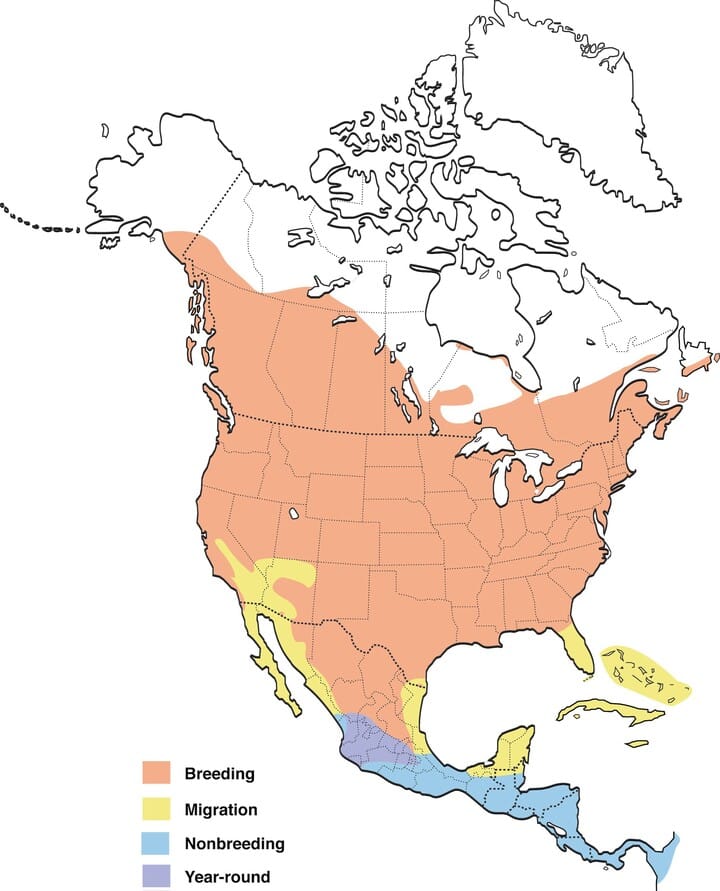

photo courtesy of Margaret WeberAgain using a range map from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, one can see that the species is now, in winter, in Central America. It can be expected back in the park in April, according to my records.

Range of Barn Swallow 3. Present only when migrating through. Many species that I (sometimes) see in Eliza Howell travel a long distance in migration twice a year. They breed north of here and winter to the south. Many warblers are in this category, including Cape May Warbler.

Cape May Watbler,

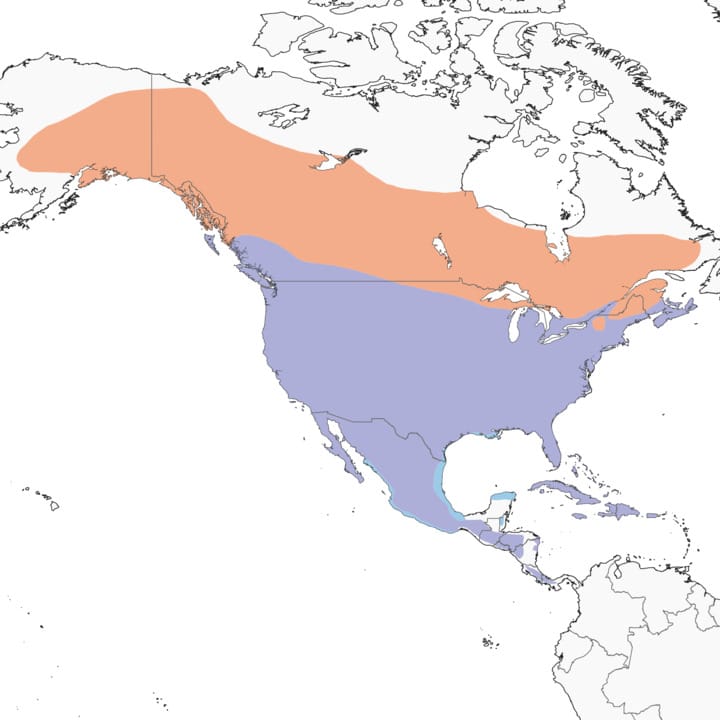

photo courtesy of Margaret WeberAs the range map (Cornell Lab of Ornithology) shows, Cape May Warbler breeds in Canada and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and winters mostly in the Caribbean Islands.

Range of Cape May Watbler 4. Present year-round. My example here is Red-tailed Hawk, which nests in the park regularly. It can be seen (and heard) during every month of the year.

Red-tailed Hawk,

photo courtesy of Margaret WeberWhile many Red-tailed Hawks (almost all of those that breed in Canada) do migrate south in the fall, they are permanent residents here. (On the maps from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, purple represents year-round.)

Range of Red-tailed Hawk On a month-by-month basis, the average number of bird species seen in Eliza Howell Park is lowest in winter and highest in peak migration months for song birds.

January = 21

February = 19

March = 32

April = 48

May = 69

June = 46

July = 43

August = 52

September = 68

October = 55

November = 33

December = 25

During this, my 20th year of bird watching in Eliza Howell Park, I plan to report periodically on bird behavior — which birds are doing what when.

-

Common Ringlet: # 23 of “23 Butterflies in 2023”

Leonard Weber

December 28, 2023

The honor of closing this year’s series on butterflies of Eliza Howell Park goes to Common Ringlet. It is noteworthy for two quite different reasons.

1. Common Ringlet is variable in appearance, even in one location, as is indicated by these Eliza Howell photos.

It is small, with a wingspan of an inch to an inch and a half. It’s seen from May through August, often low on leaves and stems, sometimes nectaring on flowers. It spends the winter in the caterpillar stage.

It shows orange when it flies, but is rarely seen with wings open when perching. There is usually a dark spot near the tip of the forewing below, but sometimes that is absent or hard to see.

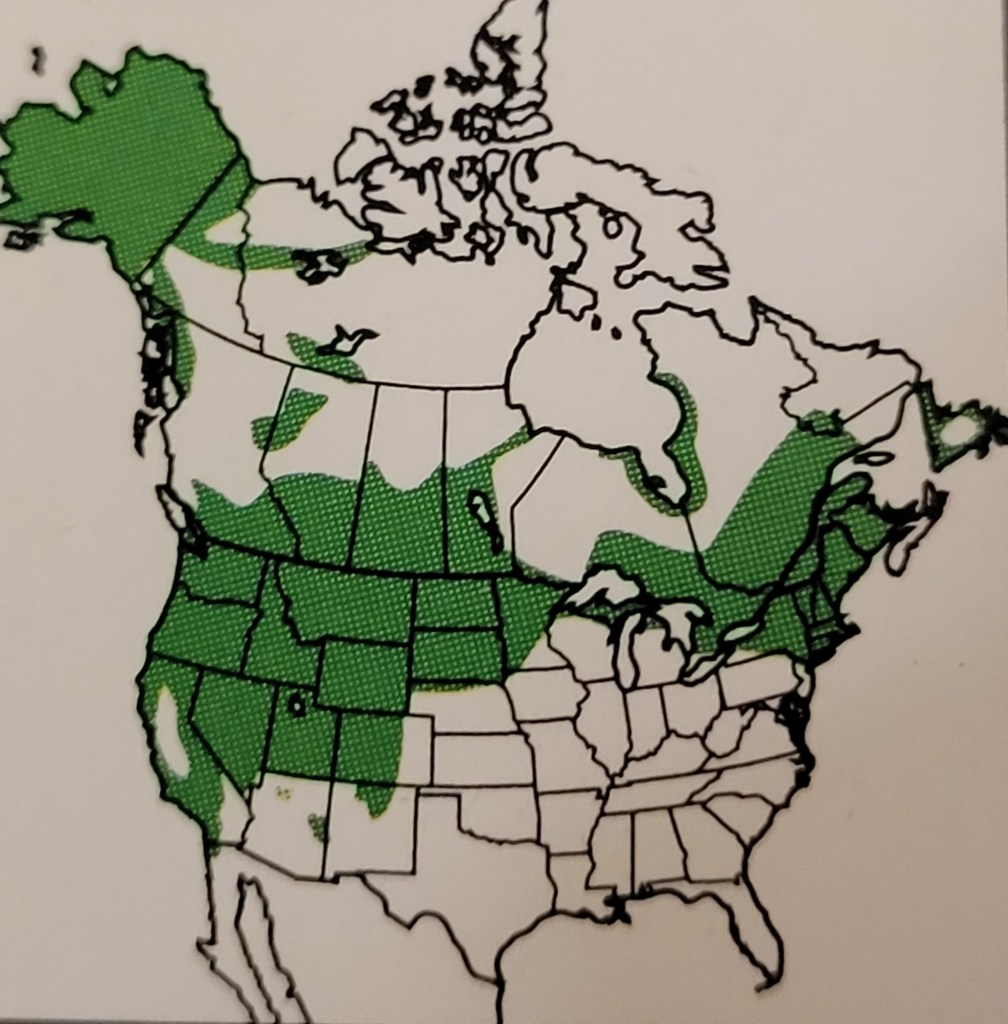

2. The second noteworthy point about Common Ringlet is that it is frequently present here in Detroit, contrary to reports about its territorial range.

It is common in Eliza Howell Park and has been since at least 2011, when I started keeping more detailed records. The sources we turn to for butterfly information, on the other hand, both the published field guides and the online reports, indicate that it is not to be found in southern Michigan.

Kaufman Field Guide to

Butterflies of North AmericaThe range of the Common Ringlet is often described as being expanding, but none of the guides that I have seen would lead us to expect to find it here. Yet here it is, in good numbers, year after year.

The southward movement from Canada through New England in recent decades is reported, but its presence in southern Michigan has not (yet) been recognized in revised range maps.

On Purple Coneflower with Goldenrod Soldier Beetle

August 2023Common Ringlet is a favorite. It is reliably present, the individual variations are worth attention, and there is something appealing about a species that doesn’t stay within the lines drawn by the lepidopterists!

-

Great Spangled Fritillary: # 22 of “23 Butterflies in 2023”

Leonard Weber

December 19, 2023

Great Spangled Fritillary is a conspicuous and quite large * butterfly that can be found every summer in the Eliza Howell Park, visiting meadow wildflowers that bloom here (*wingspan of 2 1/2 – 3 1/2 inches).

On Wild Bergamot The word “fritillary” comes from a Latin word and refers to the checkered pattern often found in this group of butterflies. “Spangled” refers to the sparkling or shiny look of this species.

Regardless of whether it is well-named, Great Spangled Fritillary definitely is pleasure to see when it shows up in the park.

On Purple Coneflower

On Butterfly Weed Despite its size, its colorful appearance, its visits to common flowers in butterfly gardens, and its coast-to-coast range, my impression is that it is not often on the “I would like to see” list of many park visitors.

Kaufman Field Guide to

Butterflies of North AmericaGreat Spangled Fritillary spends the winter in the caterpillar stage, completing development in the spring. The caterpillars feed on various species of violets.

There is only one brood a year. I see the adult butterflies most often in July.

On Purple Coneflower

On Wild Bergamot Presenting this series of 23 butterfly species has been a good way of reviewing what is present every year in the park as well as a reminder of some that I want to give more attention to.

Great Spangled Fritillary is one species that I hope to focus more on in the future, both in my own study and in pointing out to others. It is called “Great,” but it may not get the respect it merits.

-

Orange Sulphur: # 21 of “23 Butterflies in 2023”

Leonard Weber

December 13, 2023

This series highlighting 23 of the butterflies seen in Eliza Howell Park was started in January 2023. The last ones are scheduled to be posted before the end of December 2023.

Orange Sulphur is a common park butterfly, one that can be seen flying quite late in the fall. It is typically present until the end of October.

Orange Sulphur on

New England AsterThere are two Sulphurs that are regularly present in Eliza Howell: Orange Sulphur and Clouded Sulphur. They look very similar, requiring a clear look — or the review of a photo — to tell the difference.

Both Sulphers have dark borders on the upper side of their wings, but because they rarely open their wings when not in flight, the borders are not usually seen clearly.

Orange Sulphur often shows a little orange on the underside of the forewing.

On Wild Bergamot Sometimes, when the light is right, it is possible to see the dark border showing through the closed wings.

On Purpke Coneflower

On Butterfly Weed Orange Sulphur has a wingspan of about 2 inches. It is present from spring to fall, spending the winter in the chrysalis stage. It comes eagerly to a variety of wildflowers in the open areas of the park.

On Goldenrod As is clear from the above photos, Orange Sulphur is predominantly yellow (no doubt the reason this group is called “Sulphur”). It took me a few years of butterfly watching before I realized that sometimes the Sulphur is greenish white instead of yellow.

White Female on Red Clover Some (but not most) females are more white than yellow. This is also true of Clouded Sulphur and the experts that I consult for identification expertise caution that it is virtually impossible to tell the difference in the field between the white form females of the two species.

In July, I took this photo of a white female as it was just starting to fly, catching the black border on the open wings.

White Female, Orange Sulphur or Clouded Sulphur Except for the white females, it is possible, with the use of a good field guide, to tell the difference between an Orange Suphur and a Clouded Sulphur most of the time.

It is not necessary, of course, to be fully secure in identifying which Sulphur is the one on the flower in front of me in order to enjoy the sight and appreciate the butterfly – flower connection.

Orange Sulphur on

Purple Coneflower -

Berries in December: Winter Creeper

Leonard Weber

December 5, 2023

In early December walks in Eliza Howell Park, I often pause at several climbing vines growing in the woods along the Rouge River. These vines provide an unusual look in early winter — green leaves and newly ripened berries.

Winter Creeper in early December This evergreen vine is known by different names in English, including “Fortune’s Spindle.” The one I usually use is “Winter Creeper.”(The botanical name is Euonymus fortunei.) By whatever name, it provides the last new fruit of the year.

Winter Creeper is a native of Asia, introduced into this country as a garden ornamental over a century ago. During the last 50 years or so, some have escaped into the wild, the seeds probably having been spread by birds that eat the fruit. It grows only in one small area in Eliza Howell (as far as I know).

After climbing the trunk of a tree, the vine produces branches, looking like a shrub in the bigger tree. It grows 20 feet high or more.

The vine climbs tree trunks using many hairy aerial roots to adhere, similar to a Poison Ivy vine. The climbing vine trunk can get quite large.

Large Vine adhering to tree trunk The fruit clusters were closed capsules during the fall when most other fruits ripened.

Winter Creeper in the middle

of NovemberAt the end of November, the capsules open, revealing the red-fleshed seeds and attracting birds — as well as humans with cameras.

Almost every year, we get an early winter snow, clearly demonstrating Winter Creeper as a winter berry.

-

Marcescence: And Shingle Oak

Every year at this time, when most leaves have fallen in Eliza Howell Park, walkers notice that a few trees hold onto their dead leaves long past the time most have fallen.This phenomenon is known as marcescence.

Shingle Oak trees Marcescent leaves are more often found on oaks than on other types of trees. Among oaks, this occurs only in some cases and is more common in young trees than in mature trees.

There is a group of several Shingle Oak trees that has been the epitome of marcescence in the park in recent years. (Shingle Oak is called that because the wood was used to make shingles.)

A couple of the Shingle Oak trees are seen in the photo above. Here is another view of the clump (the tree in front with slghtly lighter-colored leaves is a Turkey Oak).

Shingle Oak trees with a Tutkey Oak in front The leafless tall tress in the background are also oaks, mature trees. They indicate the relative youth of the marcescent trees.

Shingle Oak leaves Based on observations made over the past several years, I think it is likely that the Shingle Oak leaves will hang on all winter, most of them not falling until March.

There are some leaves that have not yet fallen from a few other trees in the park. One mature Swamp White Oak retains many of its dead leaves,

Swamp White Oak

Swamp White Oak but I would be surprised if these leaves remained late in winter.

Some young American Beech trees show marcescence as well, but only the small ones. Beech trees and oak trees are in the same family.

Young American Beech tree Probably because it is the exception, I have long been fascinated by marcescence, by the reality of deciduous trees in this northern climate retaining their dead leaves through the winter.

In Eliza Howell Park, no species exemplifies marcescence better than Shingle Oak.

-

A November Morning Walk: 10 Stops

Leonard Weber

November 9, 2023

After a cloudy beginning, the sun appeared during my most recent morning nature walk in Eliza Howell Park, presenting an invitation to photo-record some seasonal observations.

White-tailed Deer rubbing This is deer rutting or mating season. A new rubbing at this time of the year means that a buck recently scraped the bark from this Sumac tree and then rubbed his forehead gland along the wood, leaving his scent, communicating his presence to both potential mates and rivals.

Bladdernut The leaves have fallen from Bladdernut trees by the river, but the papery shells holding the seeds remain on the tree.

Velvet Foot mushroom (tentative identification) Fresh mushrooms often appear quite late in the year, after what we typically think of as the “growing season” is over. Many of them, including this one, are on logs.

Moss and Lichen on tree limb November is a good time to check trees and logs for moss and/or lichen, especially in wetter sections of the park. I enjoy finding them growing next to each other, as here.

American Sycamore On clear days, for at least 5 months, from November until spring, I pause my walks to admire the white branches of tall Sycamore trees against the background of the blue sky. This was the first day for this stop this year.

Insect “trails” on bark-less tree One dead tree caught my attention on this walk. It is straight and strong — and totally without bark. It provides a fascinating opportunity to begin to learn about the boring insects (beetles, probably) that were active under the bark when the tree was alive.

American Sycamore seeds With the leaves now dried or fallen, the seed balls of the American Sycamore are quite visible. Most of them will hang on throughout the winter.

Blackberry Knot Gall The falling leaves also make it easier to see insect galls on the vines of some of the blackberries in the park. Inside these galls are the larvae of small wasps that will feed and grow all winter and emerge in the spring. The galls are better known than the wasps that lay the eggs, as can be seen from the fact that the wasp is known as “Blackberry Knot Gall Wasp.”

Shingle Oak A few trees don’t drop their leaves in the fall, but hold on to them all winter after they turn brown. The best examples in the park are several Shingle Oak trees.

Red Maple buds Trees are mostly dormant in the winter. Before dormancy, the buds for the next year’s growth appear. These Red Maple buds will complete development in the spring of 2024. Whenever, during the next few months, I want a reminder of nature’s cycle, a reminder that spring is coming, I can stop by this or some other tree with low branches and see buds.

—-

P. S. I also stopped for birds during this walk, seeing the first migrating Golden-crowned Kinglets of the fall and what are probably the last Wood Ducks in the park this year.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.